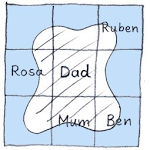

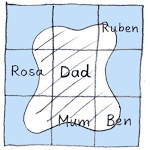

The Model – “Squares and Blob”

Everyone is affected, everyone needs support.

The mechanics and impact of traumatic events on the family and their members can be seen on the example of the addiction of one of the family members.

The Squares and Blob model below suggests a way of looking at families as “systems”, where all members of the family system are interdependent elements. We depend on each other in maintaining it, and expect for the others to fulfill their roles, i.e behave in a certain way. However, because of the interdependence, it takes the change of only one element to affect the whole system. When one family member changes, the others have to adjust their behaviour accordingly, otherwise the system may collapse.

The model below shows how families ‘work’ and affect each other:

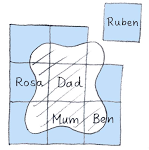

The large Square above represents the family ‘system’.

Nine Squares represent family members (the number only matters for clarity of illustration; it is not essential to find family members for each Square).

In a well-functioning family system people feel safe, belonging to and protected

by the boundaries of the large ‘family Square’. Within that Square everyone has

their own space (little Square) where they can thrive and develop – physically, intellectually, emotionally.

When something ‘big’ happens to of the members (in this case it is Dad’s drinking), everyone is affected:

The Blob above represents addiction, which seeps into, and takes over the Squares of other members, who are torn apart from each other.

Family are pushed away out of their lives and squashed into different shapes to fit in

the large family Square (like Ben) or pushed out of it if they can’t, or don’t want to fit in (like Ruben).

The case study below uses the example of a fictional family to explain how the process happens and how to change its effects.

The case study

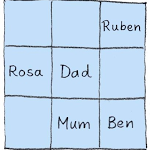

The Square below represents a family – the characters are fictional, although each of them carries bits of stories of people I worked with.

Diagram 1

Ben (age 7), is a family entertainer; outgoing, “glass half full” person, liked by all;

he is a talented musician and loves giving piano recitals to anybody at any time,

especially to Dad who was a musician himself, and is very proud of Ben.

Rosa (age 10) is “a serious one”; being the happiest in her room, she likes reading

books and writes stories herself, but can never refuse Ben’s requests to be his

audience; feels very close to Mum, they are both “tone deaf” unlike all the boys in the

family.

Ruben (age 16) is Dad’s son from the first marriage, good student, fantastic guitar

player; his dream is to have his own band. He loves his younger siblings, often

plays music with Ben and likes taking Rosa to her swimming sessions. His mum is

in Santa Lucia and he visits her during school holidays. It was hard for him in the

beginning but he eventually got to trust that the new family is for good.

Mum (age 35) hasn’t been working since the children were born. She is from Spain,

met Dad there and got married soon after finishing her degree in sociology. When

Rosa was born they came to England. Due to her husband’s successful career she

didn’t have to work and enjoyed running a family home, like her mum.

Dad (age 45) is an estate agent with many years of experience in UK and abroad.

He met Mum when working in Spain, and got divorced for her. Despite difficulties

things worked out and he managed to have Ruben in his care and have a civil

relationship with his ex-wife. Ever since he strives to be a good dad for all his

children and make sure they don’t go without. He doesn’t want to be like his dad, a

violent alcoholic who abandoned his mum and three children and was never seen

again.

The equilibrium of the family is sustained. However, the situation changes if

something ‘big’ happens. It can be a serious illness or in this case addiction.

Dad was always the one who liked his spliff in the evening, but it had never

affected their family life. After his mum died he also started drinking. Over time,

with difficulties in property market affecting the business, he started drinking more

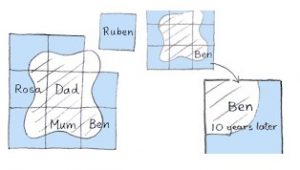

– and at some point it was impossible not to notice, as in Diagram 2 – Dad’s

drinking ‘spills over’ to become a Blob.

Diagram 2

Dad is full of shame and guilt for damaging the family, and becoming like his father,

yet cannot stop drinking. He tries to convince everybody that it is not a problem,

because he can still keep the job and provide for them.

The Blob takes over the Squares of other members and comes in between them,

causing arguments and driving them away from each other. It feels like there is

hardly any ‘space’ left for living their lives.

The metaphor translated into everyday experiences:

– Children:

• Will Mum be okay left alone with Dad? If we bring friends home after school will Dad embarrass us again?

• Why is he so angry and irritable all the time?

– Mum:

I am scared; I don’t know what is going on with the money, yet he doesn’t want to talk to me or gets angry when I mention his drinking; I feel powerless and fed up with lying and covering up for him with work and friends.

– Ruben:

I hate being here, I hate Dad for letting me down again; I pray for days to pass until I go to Santa Lucia, meanwhile I stay away, stick to my friends, hope they won’t find out about Dad. I feel sorry for the little ones, but I have to think of myself.

– Rosa:

I feel I must help Mum, she seems really upset and tired. Maybe I will look after Ben and Dad. Ruben stopped taking me to swimming, he is hardly at home. I could read more, but I worry when Mum and Dad argue so I prefer to stay with Ben and make sure he is okay. He always wants to be in the middle of things.

– Ben

I know something is wrong – what used to make people laugh and hug me, now is upsetting them, or they don’t notice me; maybe they don’t love me anymore? Maybe I should try harder to be funny? Whenever Dad is back I try to get him to play with me and make him laugh, but it is very hard now, because he is always angry.

If the situation continues, all the family members around Dad will be affected in

different ways. They have become ‘Squashed Squares’ (Diagram 2) – a metaphor for different coping strategies to fit into the new situation.

Diagram 3

Those who have a chance to escape (Diagram 3) may be able to find the new

healthier surroundings and the impact of the addiction may be less permanent and

severe compared to those who stay in the situation for years to come:

Ruben leaves for Uni and decides to live with his mum. He spends most of his

free time in Santa Lucia with her, or with her sister in Leeds where he studies. He

misses Ben and Rosa, but he can’t forgive his dad letting him down again. If he

doesn’t address this resentment, it may affect his ability to trust and commit in his

relationships.

Rosa’s and Ben’s coping mechanism will last long enough to become normalised

patterns of behaviour – quite heavily imprinted ‘Squashed Squares’ which will stay

with them into their adult lives

Rosa adopts the carer’s role, deciding that it is her responsibility to make sure her

family is okay, and that her needs are not important. When Mum has to go to work to make ends meet, she takes over a lot of house chores and looks after Ben. The task of being a parent and carer is very difficult for a young girl and she constantly feels not good enough, especially that her school results are getting worse.

Ben keeps trying to figure out how to be loved and noticed by the others. With time

his strategy will change, and from family entertainer he changes into an “attention

seeking, difficult child”. His efforts to be loved get him into trouble, which he doesn’t

understand and becomes increasingly angry and disappointed with the world.

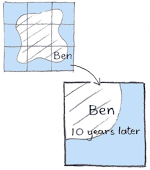

Diagram 4

Diagram 4 pictures Ben’s ‘Squashed Square’ 10 years later. He now decided that no

matter what he does he will not be loved or noticed, and people are not to be trusted.

Rather than looking for others approval it is best to do what one wants and not to

care about others. Although it is painful to be alone, it is better than being hurt. He is angry with his parents for ruining his life.

His pattern may lead to Ben becoming very defended, non-trusting and blaming

others for his anger. As an adult he is likely to attract a partner who will fit in his ‘Squashed Square’ identity – possibly someone with a ‘victim’ personality who will

easily take upon themselves to be responsible for Ben’s anger and unhappiness.

Such arrangement however is not going to alleviate Ben’s suffering. The more

the ‘victim’ partner submits, the more it gives the right for anger and resentment to

surface. Unless Ben gains awareness of his own pattern and gets help, he is likely

to look for comfort in substances and repeat the pattern of his dad. He was himself a victim of his father’s Blob, trying to live within his own ‘Squashed Square’. Like Rosa, he was a ‘carer’, helping his mum to raise the family.

This family scenario simplifies reality. Squares and Blobs are only symbols and

metaphors. But together they illustrate some useful observations shared by addicts

and family members.

The map

When we look at the S&B model as if it is a map of a territory where the Blob represents the area of conflict, we will see it as an illustration of “what happened” rather than “who did what to whom”. We can see that addiction “happened” to this family and that everyone is affected.

Looking at the diagram as it were a map allows to objectively see the situation of

respective family members.

Addict – Dad:

It may be difficult for Dad to acknowledge the effect of his drinking on his family,

but he can also see that he is as much in need of help as them. As a Blob (or drowning in Blob, as some clients interpret it) he could feel everybody moving

away from him (this is the ‘squashing’ felt from his perspective). He can also see

how much he is drifting away from the person he used to see himself as – a caring

responsible father, desperate not be like his dad.

Family members:

It is a difficult realisation that they need to do something to help themselves despite

the fact that ‘they didn’t do anything wrong’. It is a common fantasy is that as soon

as the using stops things will be ‘as before’. The map shows that the ‘Squashed Square’ happens without our conscious choice, and that it is likely to stay even if we are out of the family dynamics.

We can imagine how 20 years on Ben is full of anger with his parents for ‘what they

did to him’, even though his dad is in recovery for 10 years. His anger led him to

abusive behaviour in his marriage and he has alcohol problems himself.

Affected family members can all be likened to victims of military conflicts – without

their consent they may be exposed to events that impact on their psychological

well-being and even though it isn’t their fault, they still need to acknowledge the

damage and accept help.

In order to repair the damages it is not useful to blame or punish, as it causes resentment.

It shows that the best way forward is to abandon the framework of victims and

perpetrators, and see only the casualties in need of help to move on.

Stopping the pattern

The model and the case study demonstrate how patterns can repeat from generation to generation.

Many addicts discover that they have more than Blob identity, that they were

the Squashed Squares in their childhood, like Dad, and that it contributed to their

unhelpful coping patterns and in effect, addiction. For all family members it is a relief to understand that the strategies and behaviours they adopt are not wrong, or stupid, they were just the best they could find at the time. Once they understand where the problem lies they can start to work to regain their Square Shape, just like the pillow made from intelligent foam will, if shaken around a bit. They can stop the cycle.